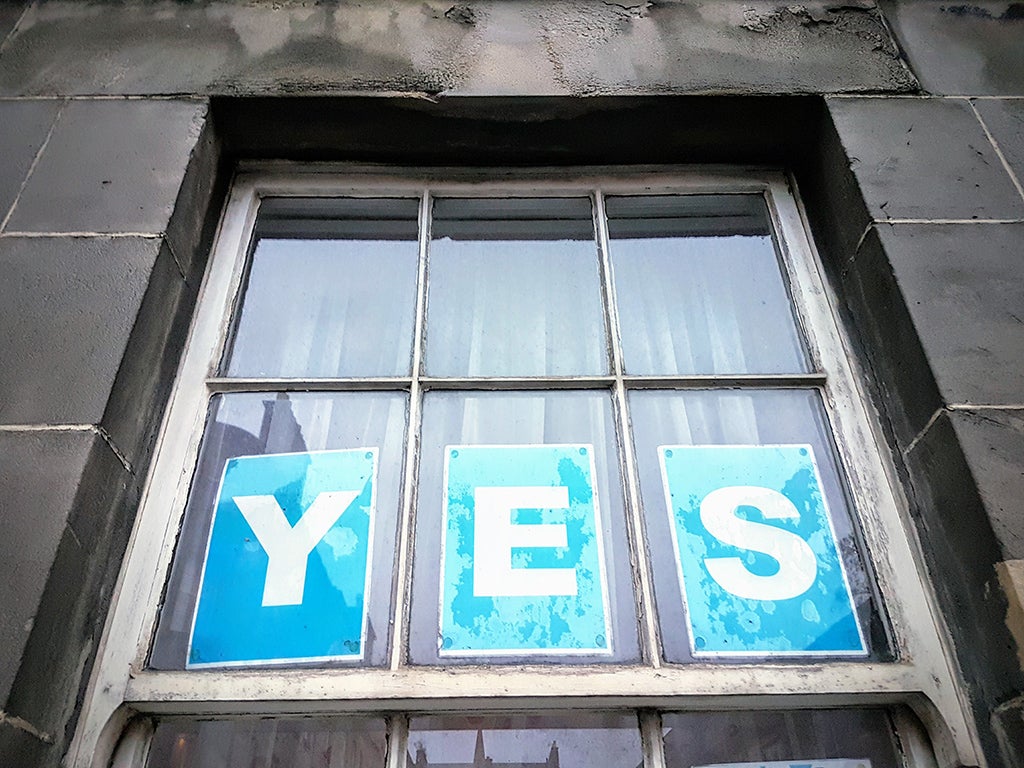

Support for Scottish independence has recently surpassed that for the Union according to the Britain Elects poll tracker – albeit by a narrow margin. If a second referendum was held today, 50.8 per cent of Scots would vote to leave the UK, while 49.2 per cent would vote to stay. Last October, 49 per cent backed independence, while in May 48 per cent did. The previous time a majority of Scots said they’d vote Yes was in April 2021, and even then, as Alex Salmond and Nicola Sturgeon joined battle against each other, support was falling from the highs of 2020.

I’m not exactly gazing into a crystal ball when I inform you that Scotland is deeply split but the 50-50 figure masks a forgotten third. The detailed data shows that 70-80 per cent of Scots are resolutely committed to Yes or No and are unlikely to change their minds. If you were a frank strategist advising either campaign you’d be loudly saying behind closed doors that they should ignore these voters; they’re on side. They may need a nudge to go out and vote but resources and attention should be focused on the undecided – the 20-30 per cent who do not know how they’ll vote, and have been in this position since the 2014 referendum.

There’s a significant amount of evidence showing why these voters are undecided and why they may be easier targets for a future No campaign than a future Yes one. Economic anxiety was central to the 2014 campaign. It was what Gordon Brown led on in his final pitch to voters in Glasgow. Anxiety over the future of pensions, the pound and the public finances sent more voters to the No side than to Yes.

Issues of Britishness vs Scottishness are the preoccupation of those already certain about their vote. And polling conducted for the admittedly pro-Union think tank Our Scottish Future suggests economic anxieties remain alive.

Yes voters, and Scots in general, favour the retention of a common UK social security system and a soft border between England and Scotland in the event of independence.

But Eddie Barnes, Our Scottish Future’s director, sounded a note of caution on his Substack: “Simply having the right building blocks in place, and then pointing to them, is not going to be enough for Yes voters to change their minds and agree they want to remain in the UK. They may like the parts, but they don’t like the sum. And the sum needs work.”

There is hope among the Yes campaign that the issue of Brexit may nullify economic anxieties and push voters towards independence. In Scotland, 62 per cent voted Remain – making it the most pro-EU of the four nations. Following the Brexit vote, well-sampled polls showed a slim majority of Scots clamouring for independence and a significant number of people switching sides. Although passions have cooled since 2016, there’s no doubt the issue had political currency.

But will it in the future? By the time of any future referendum the UK may have a Labour government, and a closer trading relationship with the EU to boot. And Brexit may not prove the game changer that the Yes side hopes – and may need.

[See also: Most voters want the UK to rejoin the EU. But there’s a catch]