It’s December 2021 and the Republicans, France’s establishment conservative party, has unveiled its candidate to challenge Emmanuel Macron in the 2022 presidential election. Her name? Valérie Pécresse.

Pécresse does well in the media rounds. She is refreshing – and voters see it. She shoots up in the opinion polls, so much so that she’s neck-and-neck with Macron, if not ahead, in some of the run-off surveys. As Pécresse eclipses Marine Le Pen in January, she gets people talking – including me. I suggest on the NS’s France Elects podcast that she would be a better unifier of the anti-Macron vote than Le Pen (if, that is, she maintains momentum).

But it was not to be. Pécresse won less than five per cent of the vote, conceding minutes after the polls closed.

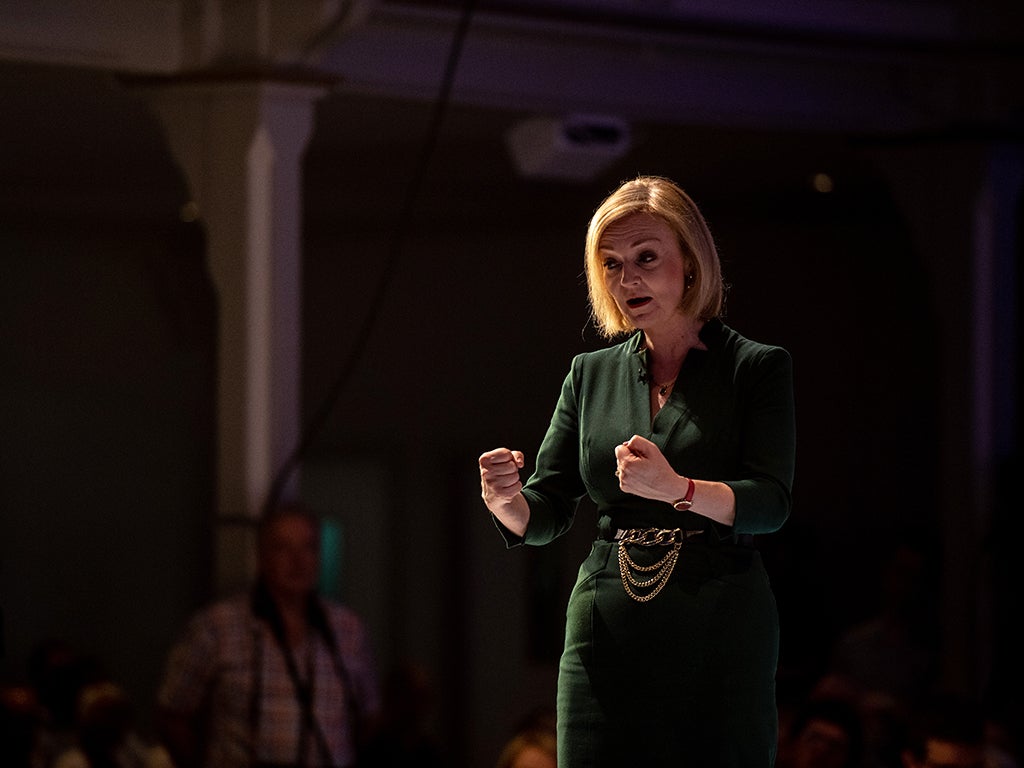

What happened in France is a good example of the temporary excitement that voters often feel about fresh candidates. In the US, too, wall-to-wall coverage of party conventions trends to generate a temporary boost for candidates among low-attention voters and the party base. This makes me wonder whether we might be about to witness the same phenomenon in the case of Liz Truss.

If we trust the polls, then there is little doubt that Truss has won the Conservative leadership election and will succeed Boris Johnson as prime minister on 5 September. Among the public, however, she is a bit of a non-entity – or, at least, was until recently.

Truss started the race far behind Rishi Sunak in terms of name recognition and is only now starting to gain traction. Labour’s poll-lead over the Tories is narrowing as voters enter a post-Johnson mind-set and quietly reset their attitudes. Those who voted Conservative at the 2019 election and then moved into the “undecided” or “wouldn’t vote” bracket are now returning to the Tory fold. And that alone has been enough to narrow Labour’s lead from nine points to five points.

New prime ministers tend to enjoy a “honeymoon period”. For the uninitiated, this is the time immediately after a new leader enters office when open-minded voters are willing to give them the benefit of the doubt. Theresa May, David Cameron and Gordon Brown all benefited from it.

But all honeymoons end, be it after six months, as was the case for Brown, or a year, as was the case for May. Johnson enjoyed neither a honeymoon nor a comedown period. The public already had a firm view of him and were unwilling to shift. He represented one side of the Brexit divide and did little to try to shift perceptions. Swing voters didn’t move towards him and then away again. Rather, Tory leavers and Labour leavers welcomed his arrival and then backed him at the ballot box.

So what of Truss? Voters are no longer as defined by the Remain-Leave divide as they were during the Brexit wars. A new prime minister with an initial message of unity has the capacity to appeal.

It’s hard to say how long that might last. If Truss enters No 10, she will immediately face daunting political and economic challenges. She will inherit a party not just behind Labour in the polls, but behind on some of the most important metrics to voters – the cost of living, the economy and even immigration. But these low bars of approval are precisely why Truss may easily out-perform expectations and enjoy net-positive approval ratings.

Any honeymoon, however, will likely prove short-lived. Voters are looking for answers and action, with inflation already at its highest level in 40 years (9.4 per cent) and forecast to rise further. Truss’s reluctance to promise further economic support beyond tax cuts gives Labour an opening.

But Truss's potential honeymoon period may represent the Tories’ best, and perhaps only, hope of winning the next general election. After that, the only way may be down for Truss.

[See also: Keir Starmer is letting a crisis go to waste]