The year 2023 will be monumental for English local government. Large councils boasting big budgets, which were last elected in 2019 amid the Brexit wars, will be up for grabs on 4 May.

The opinion polls don’t bode well for the Conservatives. In 2019, the Tories were already losing ground to insurgent parties – the Greens or an organised band of independents – though losses to Labour were limited. This time around, however, it is Keir Starmer’s party that will likely be the biggest winner – crystallising the sense that it is heading for government, and that, as Ken Clarke put it, it’s “about time the social democrats had a turn and gave us a rest”.

If the Tories’ losses are on the scale of the forecast, answers will be demanded of Rishi Sunak. Though the Prime Minister has only been in office for three months, speculation about his future has already begun – not least because of reports that Boris Johnson is once again on manoeuvres. The new Conservative Democratic Organisation, regarded as a front for Johnson’s comeback, claimed, much like the Corbynite Momentum, that it wants to “ensure the Conservative Party is representative of the membership and fairly represents their views”.

Under this scenario, Sunak could be forced out after losing a slew of seats in both Red and Blue Wall England, and be replaced by the man who kept them together in 2019. But while this logic may appear sound, does it reflect the realities of public opinion?

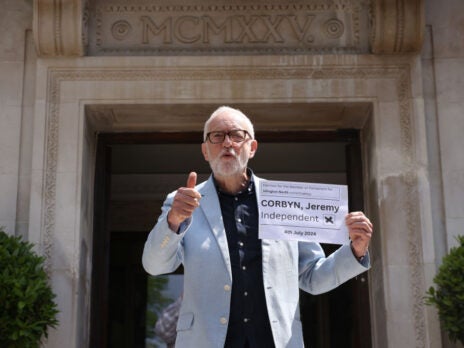

The first thing to note about Boris Johnson is that he was never truly popular as prime minister: voters consistently had an unfavourable opinion of him. What mattered was that his primary opponent, Jeremy Corbyn, was even more unpopular. And what also mattered was that the margin between Johnson and Corbyn was greatest in the marginals that mattered, the Leave-voting, traditionally Labour constituencies in northern England and the Midlands. Corbyn’s unpopularity, combined with the voters’ desire to “get Brexit done”, was what allowed Johnson to win the Tories’ largest majority since 1987.

But since then, Johnson’s popularity, both nationally and in marginal seats, has collapsed. In fact, at the start of 2022, modelling by the New Statesman found that Johnson’s Tories were polling worse in marginals than in the country at large. The former prime minister himself was the initial driver of the Tory disillusionment that has helped Labour achieve a 20-point poll lead.

Sunak is similarly not a popular Prime Minister: more Brits dislike than like him. But the gap between him and Starmer is smaller than the gap between Labour and the Tories. Brand Sunak may not be the force it was in 2020 – when he became the most popular politician in the country as chancellor – but it’s still the best asset the Conservatives have.

Johnson’s credibility, meanwhile, is in a worse state. Some 65 per cent of voters have an unfavourable view of him, while just 29 per cent as of October* hold a favourable opinion. But while Sunak’s fanbase is broad, Johnson’s is narrow. While the latter is more popular among the Tory base, he has lost all support among 2016 Remain voters. Sunak, by contrast, hasn’t.

There are many Remain voters in southern Conservative shire seats, not to mention in the six Tory seats in Scotland. Johnson may be more popular among Leave voters, and would therefore perform better than Sunak in the Red Wall, but he risks being punished in the commuter belt seats won by David Cameron in 2010, not least in his own backyard (Uxbridge and South Ruislip).

Patrick English, of YouGov, did a rather brilliant plot of who voters would prefer as prime minister. In it he found data that supports all of this. Sunak is preferred to Johnson as prime minister by most voters, but he performs worse among Leave-voting constituencies along the Lincolnshire coast, South Yorkshire and the Midlands.

Johnson has appeal, but it’s confined to the Tory base and only a certain section of that base. If Tory parliamentarians lose their nerve in May and inaugurate Johnson once more, they may narrowly keep their Morleys and their Grimsbys but confine to oblivion their Cambridgeshires, their Swindons and their Somersets.

* Though the data comes from October, the composition in support for Sunak doesn’t appear to have shifted.