“Do you think it’s time for a change?”

This is classic push-polling – a bid to influence a prospective voter by way of a leading question, all under the guise of a so-called impartial poll. A simple question like this forces the respondent into a binary. ‘Yes I think it’s time for a change’ (the voter is led down the garden path), ‘so who might that be?’ (in this case logic demands it could be anyone but the Conservatives). This is a squeeze tactic, and it works.

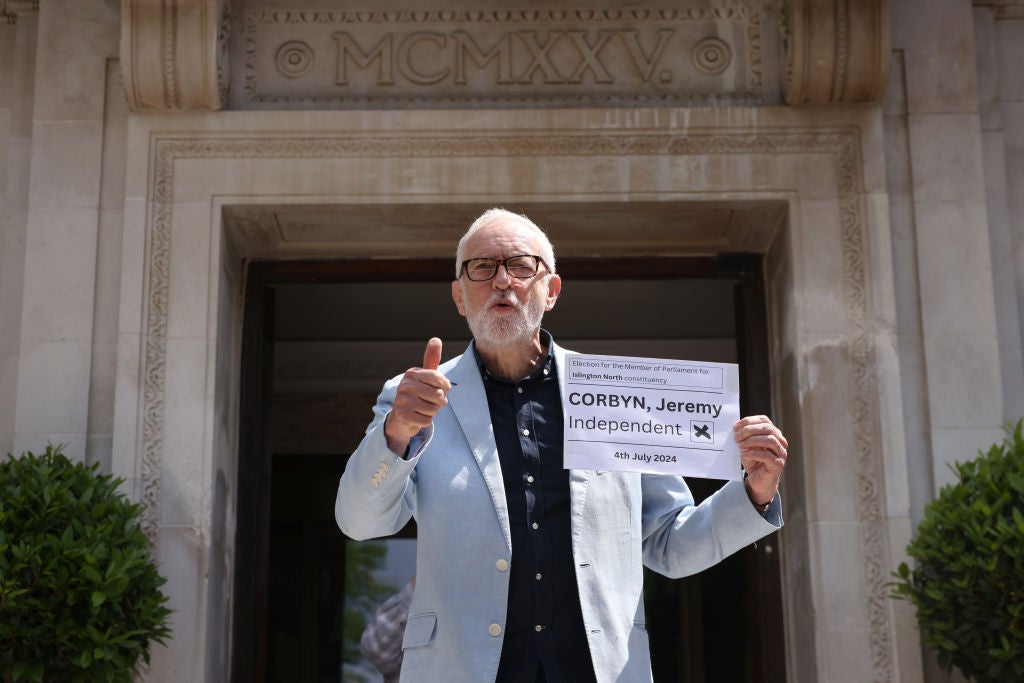

In Islington North, where a Labour candidate is facing the former party leader (but now independent candidate) Jeremy Corbyn, how might a question like this play out?

First, some context: Corbyn trails Labour by 14 points, according to the findings of a Survation poll in the final two weeks of the 2024 general election campaign. And despite what the left-wing Novara Media say, a 14 point lead is not “close”. It’s in fact rather wide. Corbyn has a strong basis in Islington North – he is personally very popular. But not enough, it seems, to strike through and claim the seat off Labour.

The overall numbers are as follows: Labour are at 43 per cent (down 22 points on 2019), Corbyn is at 29 per cent, the Liberal Democrats at 7 per cent (down eight), the Greens at 7 per cent (down one), and Reform and the Conservatives on 6 per cent each. The sample – 400 so-called committed voters – leaves a slightly larger margin for error than what we would normally expect. But not enough to alter the narrative entirely. As I wrote last month, three-in-ten plumping for Corbyn would be about par for the course for a popular incumbent shedding his party and standing as an independent.

But we are one week out, and the numbers can change. Michael Portillo, of Portillo Moment fame in 1997, was (according to a Guardian poll) 3 points ahead in his Enfield Southgate seat one week from polling day. He ended up losing it, 3 points behind. So poll movement isn’t impossible. But Corbyn is still far further behind where Portillo was.

But there is one data-point that does work in Corbyn’s favour, and it refers back to my opening: forced choice; or making this a two horse race between an unknown Labour entity and Corbyn.

When voters are forced to choose between the better-known Corbyn and the lesser-known Labour candidate, Corbyn wins 55 per cent to 45 per cent. That could just be name recognition. But when voters are asked how favourably they feel towards certain figures, 56 per cent feel favourably towards Corbyn. And 39 per cent feel favourably towards Keir Starmer.

On personality terms, Corbyn has an advantage. Exploiting that is the way for him to win. If the election were a pure personality contest – heck, were it a by-election – Jeremy Corbyn would walk it.

But it isn’t. Labour leads by 14 points, because voters vote in General Elections like this with more than just personality in mind. The question now is to what extent will the numbers narrow if enough voters are encouraged to think with the squeeze question in mind – Corbyn vs. Labour? Because the numbers suggest it could shift the dial. One quarter of prospective Labour voters say they prefer Jeremy Corbyn to the current Labour candidate. Not enough in isolation to win it for the independent incumbent. But enough to bring the result into doubt.

Corbyn can win. It’s not likely. But his chances aren’t nought, either.