New prime ministers typically enjoy a honeymoon period in public opinion when they enter Downing Street. Voters project on to them a belief that they can be all things to all people. Theresa May enjoyed this in abundance after becoming PM in 2016, as did David Cameron and Gordon Brown.

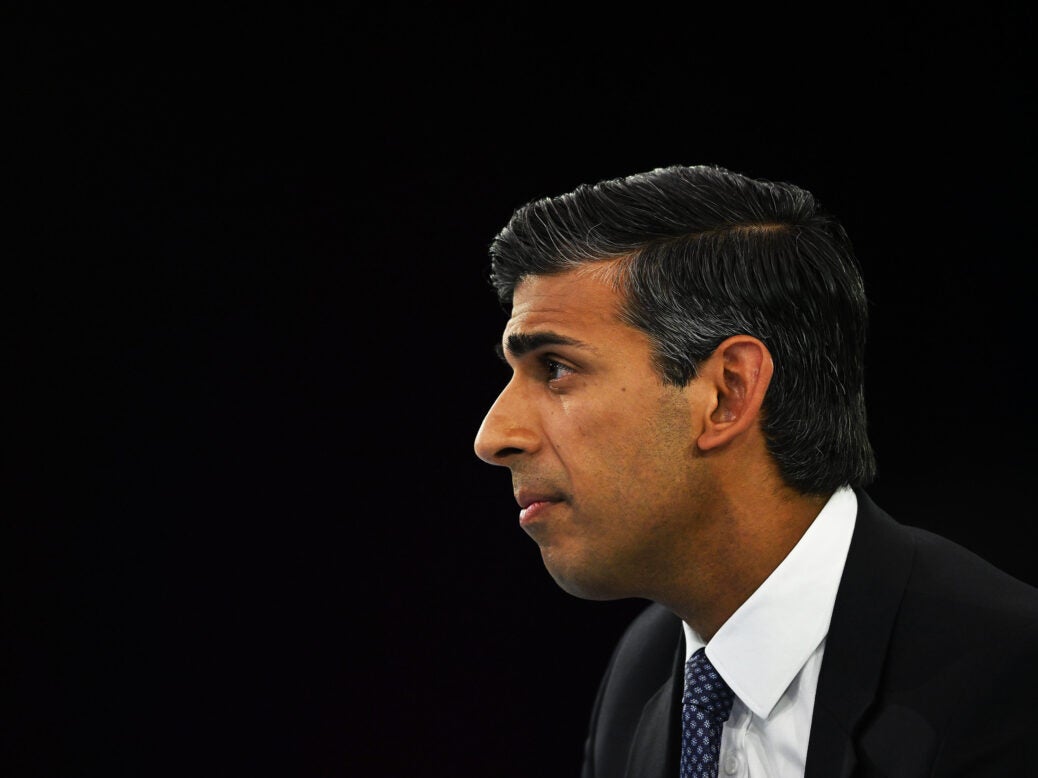

Rishi Sunak is also, to an extent, benefiting. Though he is no longer the most popular politician in the country, he is more liked than disliked with voters. When pitted against Keir Starmer on the economy, he sometimes leads. Perceptions of competence exist, though they are not overwhelming. In short, brand Sunak still has currency with the public.

Yet the Tories have so successfully trashed their reputation that their recovery against Labour is far more muted when compared with Sunak’s improvement on Liz Truss. While Sunak in his first week as Prime Minister was 17 points ahead of Truss on favourability with the public, the Conservatives’ vote share has only risen by seven points (according to a Redfield and Wilton poll).

When Sunak entered No 10 on 25 October, Labour’s lead was 29 points. The most recent series of polls, two weeks into Sunak’s premiership, still put Labour around 20 points ahead. Consider that between 10 per cent and 15 per cent of 2019 Tory voters are now saying they will back Labour at the next election – unchanged over recent months – and you have a recipe for a permanently lower ceiling of support for the Conservatives.

Voter transfers – those defecting from one party to another – happen regularly and more often than some people think. At the 2019 general election, 3 per cent of 2017 Tory voters went Labour – against the grain. And in 2017, 7 per cent of 2015 Labourites went Tory – again, against the grain. At present, however, there is little evidence that the number of 2019 Labour voters considering the Tories is anywhere close to this.

In one respect, Sunak’s hands were already tied before he entered office. So extensive has been the damage to the Tory brand from a litany of scandals that even a more popular leader – and leaders matter – has limited impact. The Labour lead is down from 29 points to 20 points, and the party is now merely projected to win a large landslide victory (as opposed to an elephantine one). The likelihood of this enduring until the next election is, in my view, low but it doesn’t incentivise Tory waverers to give serious thought to the likely losers of the next election.

Sunak’s qualities are not enough to rectify the Conservatives’ relationship with voters. As I’ve written previously, perhaps the only way to reset relations is for the party to be defeated at the ballot box, so that it is forced to rebuild. And with the government’s austere Autumn Statement the next landmark event, there isn't much in the news cycle to help Sunak transform the Tories’ fortunes. His opening weeks in office have proved that the public isn’t just voting for the personality at the top – they vote for the party too.

[See also: The new constituency boundaries for England and Wales]