More than one million working days may be lost to strikes in December, according to trade union estimates. Such a figure, if realised, would rank 2022 as the worst year for strikes since Margaret Thatcher was prime minister.

But how do the public feel about it? Data points reminiscent of bygone days of industrial action will inevitably inspire emotive responses – either of worker solidarity or renewed antagonism towards unions.

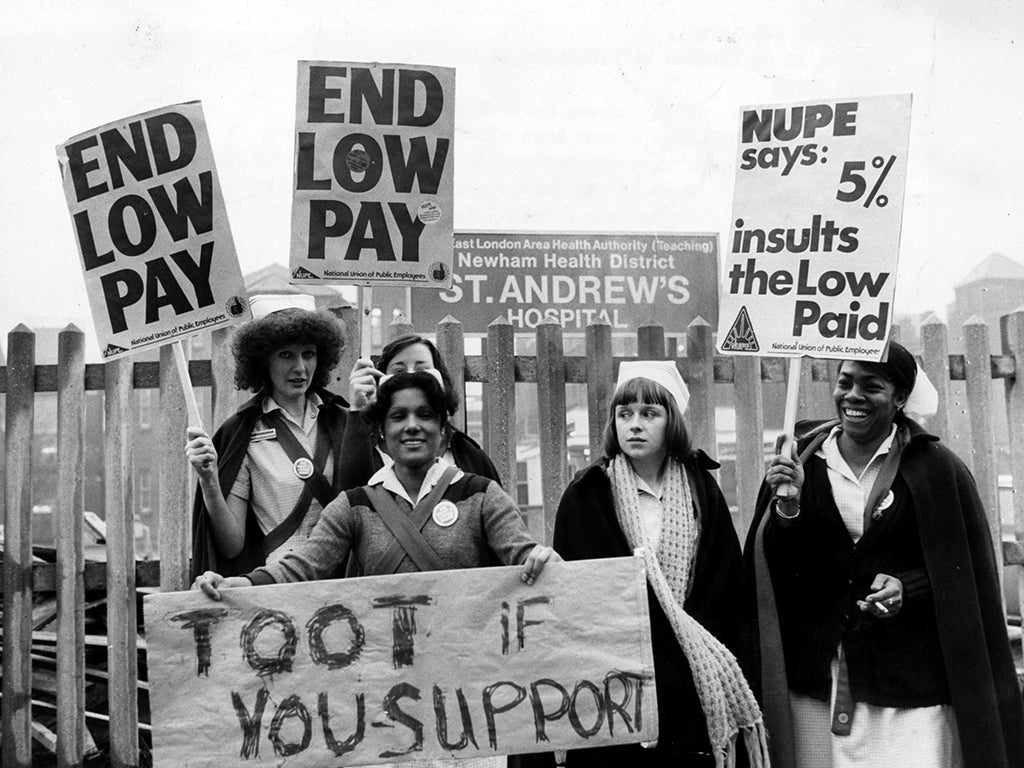

The reasons for these strikes are clear – after a decade of weak growth and pay stagnation, inflation and the spike in energy prices have triggered a full-blown cost-of-living crisis. But industrial disruption doesn’t always push social attitudes in the direction readers of the New Statesman may expect. Take the following Gallup polls, for example. At the peak of the so-called Winter of Discontent of 1978-79, 51 per cent of Britons were convinced the trade unions were considerably, or to a great deal, controlled by communists. Just 8 per cent rejected the view outright.

Fast forward to July 1984, a few months following the start of the miners’ strike: sympathy for the strikers, at 33 per cent, trailed that of sympathy for the employers, at 40 per cent. By December, the gap had widened. Sympathy for the miners fell to 26 per cent, whereas support for the employers had risen to 51 per cent. As things were wrapping up, with Mrs Thatcher seemingly unshakeable by an industry in uproar, approval of the methods used by the miners amounted to a measly 7 per cent.

This was Britain experiencing its worst strikes in postwar history. On issues of industrial relations, the Conservatives almost always led Labour in the run-up to and aftermath of 1984. But snap back to today, and we find British attitudes aren’t what they used to be. Some 46 per cent of Britons, for instance, according to a YouGov poll for the Times, blame the government for industrial action soon to be taken by nurses and ambulance drivers. Just 17 per cent blame the trade unions. And when it comes to competence, the government’s ratings are at rock bottom.

Much of the sympathy for strikers appears to be more the fault and failure of the government, rather than the success of the unions. Nearly half – 48 per cent – say the government has handled the strikes unreasonably, compared with just 24 per cent who say it has handled them well.

[See also: Chester proved Labour’s landslide chances are real]

When you ask the same question of trade unions, however, you don’t find a reversal in fortune. Instead, just 33 per cent say the trade unions have thus far have handled strikes, pay disputes and overall worker negotiations well, compared with 43 per cent who say they have handled them badly.

You could look at these figures and say the trade unions have a nine-point lead over the government on handling pay disputes. That in and of itself is pretty stark, not least when one considers the historic attitudes of the median voter.

But that median voter is a fickle sort, and one shouldn’t get carried away. When asked in the summer, Britons showed overwhelming sympathy for certain professions seeking better pay deals. And, on occasion, most Brits have continued to support them. But note I write “certain” there, and “on occasion” too – not all, not forever. Look at this, a chart I replicated from YouGov.

What we see here is that levels of public sympathy and support for strikes really come down to who, exactly, is striking. To voters, not all blights are created equally. While support for the nurses walking out is overwhelming, for train drivers and university staff it is very much a minority viewpoint. Railway support staff, perhaps the biggest advocates of all for industrial action, have the sympathy of a little under half the country, and the support of just 40 per cent of it.

That isn’t to say 60 per cent are necessarily opposed to rail workers walking out. Rather, it’s that the country isn’t totally in favour of them, either. While there is support for strikes, it is muted and profession-dependent. This isn’t the Britain of the 1980s, of quiet support for the hard-line methods of a Conservative leader. But it isn’t a nation rallying to the cries of collective action just yet either.

[See also: Voters want radical constitutional change, polling shows]