Isaac Levido, one of the chief masterminds of the Conservatives’ 2019 general election victory, recently spoke to Rishi Sunak’s cabinet on potential comeback strategies. Levido, the Sunday Times reports, pointed out that a third of the electorate at present is “soft”: 20 per cent are undecided, and the remaining 13 per cent or so may change their minds. This piece of the electoral pie, he is suggested to be inferring, is up for grabs.

Focusing on Sunak’s five pledges to halve inflation, boost economic growth and cut NHS waiting lists, the national debt and small boats could, Levido said, yet secure the Tories a fifth consecutive election victory.

Let’s assess this. The situation for the Tories is, at present, dismal. Sunak has been Prime Minister for just over three months now. And despite what was touted by some as his personal appeal, the polls have yet to significantly narrow. Labour would still win a landslide if an election was held today. The Conservatives have not led in a single opinion poll for more than a year.

Much of Labour’s lead comes as a consequence of Tory voters staying home, although not all. More than one in ten of those who went Tory last time now say they would back Labour – the equivalent of 1.5 million votes. The assumption that these Conservatives can be won back during the next election is, however, a reasonable one. Voters returning home is what won Labour its third term in 2005 and the Tories’ 2015 and 2019 victories. Bases can be rallied – history says so.

But today things are different. The Tory base is effectively indifferent to the prospects of a Keir Starmer victory. Forty-five per cent told an exclusive Redfield & Wilton poll for the New Statesman that they would either be happy with a Starmer win or unbothered by it. Feelings such as these bode ill for parties in desperate need of a revived base.

Which explains, perhaps, why Levido believes a relentless focus on measurable pledges, rather than more abstract strategies, could swing the waverers.

But one wonders whether staking everything on these pledges is more straw-grasping than serious strategy. The current polling situation bears only weak similarities to past midterm blues, such as 1990 or 2013. There are fundamental differences between then and now, which make a comeback for the Tories far harder.

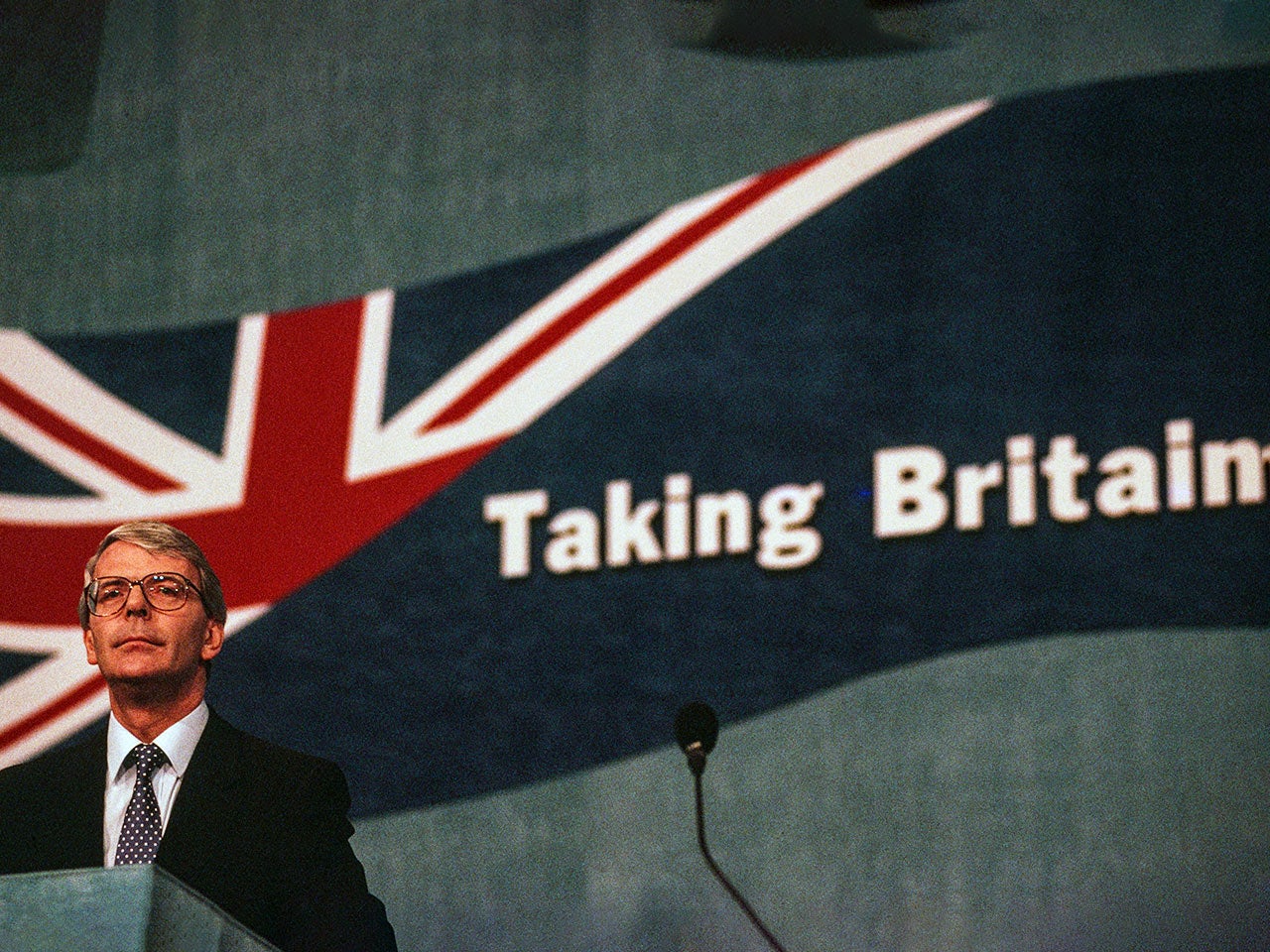

In 1990, as John Major took over from Margaret Thatcher, the Conservatives led Labour on the economy – and by a significant margin. Right up until election day in 1992, the Tory lead in this area was almost unthreatened.

In 2013, while the Tories were taking a hammering from Ukip in their coastal seats, they nevertheless led Labour on the economy, just as David Cameron led Ed Miliband on personal likeability.

In 2022-23, Labour leads the Tories nationally (by around 20 points) and on the economy, the first time the party has done so since 2007. In view of all this, comparisons with past “comeback kid” elections are null and void. On what is traditionally their strongest suit – the economy – the Conservatives are at rock bottom. Recovering from this will require more than just stemming the present tide of inflation.

But let’s say the economy improves, and voters feels a semblance of stability. Would the Tories benefit? I was struck by one survey brought to my attention by Keiran Pedley of Ipsos. Unsurprisingly, 70 per cent of the public believe the government has been doing a bad job of running the country, while just 21 per cent think it has been doing a good job. But the killer statistic is this: 66 per cent of Britons agree that “it is time for a change at the next election”, including some who thought the government had been doing a good job. In theory, a Tory recovery may look feasible but, after nearly 13 years in office, how can they overcome figures such as these? It might be better to concede the simple truth: they can’t.

[See also: Given Labour’s poll lead, are the Tories finished? – State of the Nation]