Should the Lib Dems be doing better? John Curtice thinks so. At a fringe event at the party’s conference in Bournemouth this week, the polling expert addressed members and argued that they need to be bolder, most notably on Europe.

At present, Britain Elects has the Lib Dems polling at 11 per cent, a point down on their 2019 vote share. It’s hard to disagree that Europe remains a key issue for a significant share of voters. While the cost of living is the top issue for every strata of society – a fact that has nullified most attempts by the Conservatives to shift the focus to “small boats” – Brexit is still central to plenty who voted Remain.

But I have to disagree with John here. He emphasises that some Remain-supporting Lib Dems are now moving to Labour, a transfer of support that he claims wouldn’t be happening had the Lib Dems sought to redefine the Brexit debate. In Con/Lab marginal wards and by-elections there is enough evidence pointing to precisely this: Labour absorbing the anti-Tory coalition. But it is my contention that a louder anti-Brexit campaign by the Lib Dems wouldn’t shift this.

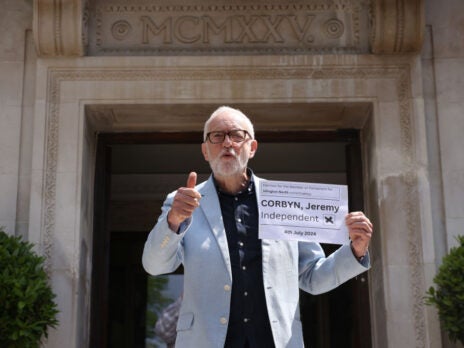

These are voters in Con/Lab marginals who would naturally shift Labour’s way in a general election campaign. And not only this, the end of the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, who alienated plenty of liberals, allows them to countenance voting tactically for Labour once more. Since there are more Con/Lab contests than Con/Lib ones, the inevitable consequence will be a decline in overall national support for the Lib Dems: a squeeze on non-Con/Lab supporters in Con/Lab seats.

[See also: Who's afraid of a Lib-Lab coalition?]

The reason for the squeeze on the Lib Dems is not the party's relative silence on Brexit but an overriding nationwide antipathy towards the Tories (to Labour’s benefit). The primary issue for most voters is not Brexit. It remains the cost of living.

It is also my view, however, that for the benefit of the Lib Dems, all this doesn’t really matter. At the 1997 election, while the Lib Dems shed a net 750,000 votes, they gained 28 seats. The most profitable opportunity for the Lib Dems in a period of Conservative decline is not in national polling but in Con/Lib battlegrounds.

At the local elections in May, we saw signs of strong Lib Dem support in their old pre-coalition heartlands and in the so-called Blue Wall of affluent, pro-Remain Tory seats in English suburbia. Four months ago, in North Devon, the Lib Dems obtained 9,000 votes to the Tories’ 6,000. In Chichester, while the Tories managed to attract 9,800 supporters, the Lib Dems amassed 15,200. Labour could only enthuse 3,000. In Wantage, Oxfordshire, the Lib Dems notionally led the Tories across the seat, with nearly 20,000 votes to the Tories’ 12,000.

The May local elections showed us the Lib Dems' strength in a cross-section of Tory seats, not just Remain-voting ones. And while Cambridgeshire and the Home Counties will inevitably be replete with soul-searching Tories (ie the voters the Lib Dems need to strike gold), this is only half the story.

The kind of voters leaving the Lib Dems for Labour appear to be doing so in seats where the Lib Dems are not competitive. There is little evidence to show this happening in seats where it is the Lib Dems who are competitive, not Labour. Herefordshire, Devonshire and Somerset are not bastions of English Remainia either. They voted Leave. And yet it is these counties that contain the constituencies that could help return the Lib Dems to something like their pre-coalition strength.

A party of all things to all men recasting itself as a “Rejoin” front wouldn’t be doing itself any favours (even if it won the odd additional vote from Labour in, uh, Bradford East). Brexit is a debate for the next parliament.

[See also: Tamworth's the by-election which will tell us everything]